Why we invested in Upside Robotics

by Carina NamihYou know you’re onto something when a Canadian farmer, who’s worked the land for 30 years, gets emotional showing you robots on his phone.

I’m standing in his cornfield in November, wind biting through my jacket, watching small autonomous machines navigate through the rows. He’s beaming as he points at his phone, showing me the real-time data stream from each robot.

“I get to stay warm inside, enjoy my coffee, and watch these little guys work hard out here.” Then he looks at his son: “It means this guy might actually be willing to take over the farm.”

Another farmer sent a handwritten letter to Canada’s Minister of Agriculture raving about the product: “Using Upside feels like having an agronomist in the field every day.”

This is what product-market fit looks like in agriculture - an industry that has resisted disruption for decades.

Why farming is finally ready for disruption

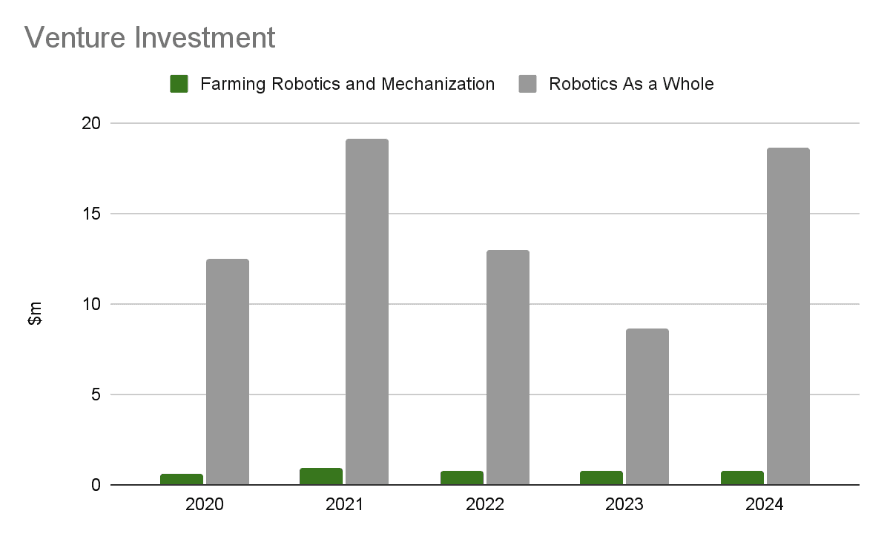

Agriculture has remained fundamentally unchanged for longer than almost any other major industry. While manufacturing and logistics absorbed tens of billions in automation investment over the past decade, farm robotics attracted 14x less VC capital despite serving a similarly sized market.

The reasons were valid. Huge incumbents like John Deere dominated with heavy machinery that was nearly impossible to retrofit. Investors got burned on capital-intensive bets like indoor farming. And until recently, the unit economics for robots robust enough to survive real field conditions simply didn’t work.

But several forces have converged in the last two years that change everything:

Hardware costs collapsed and AI caught up

The constraints that made precision field robotics impractical have fallen away in the last two years.

Several hardware cost curves collapsed at once:

- Precision GPS: $10,000 → $200

- Flow sensors: $3,000 → $50

- Solar panels: $350 → $70

- Vision cameras with onboard inference: ~$150

At the same time, edge compute finally caught up with mobile robotics. Embedded vision hardware can now run real-time inference directly on the robot. New radio mesh networks cover kilometre-scale fields. Starlink makes remote connectivity practical.

Hardware is no longer the bottleneck. Combined with AI that can process complex environmental variables in real-time, this shift unlocks an entirely new category of field robotics.

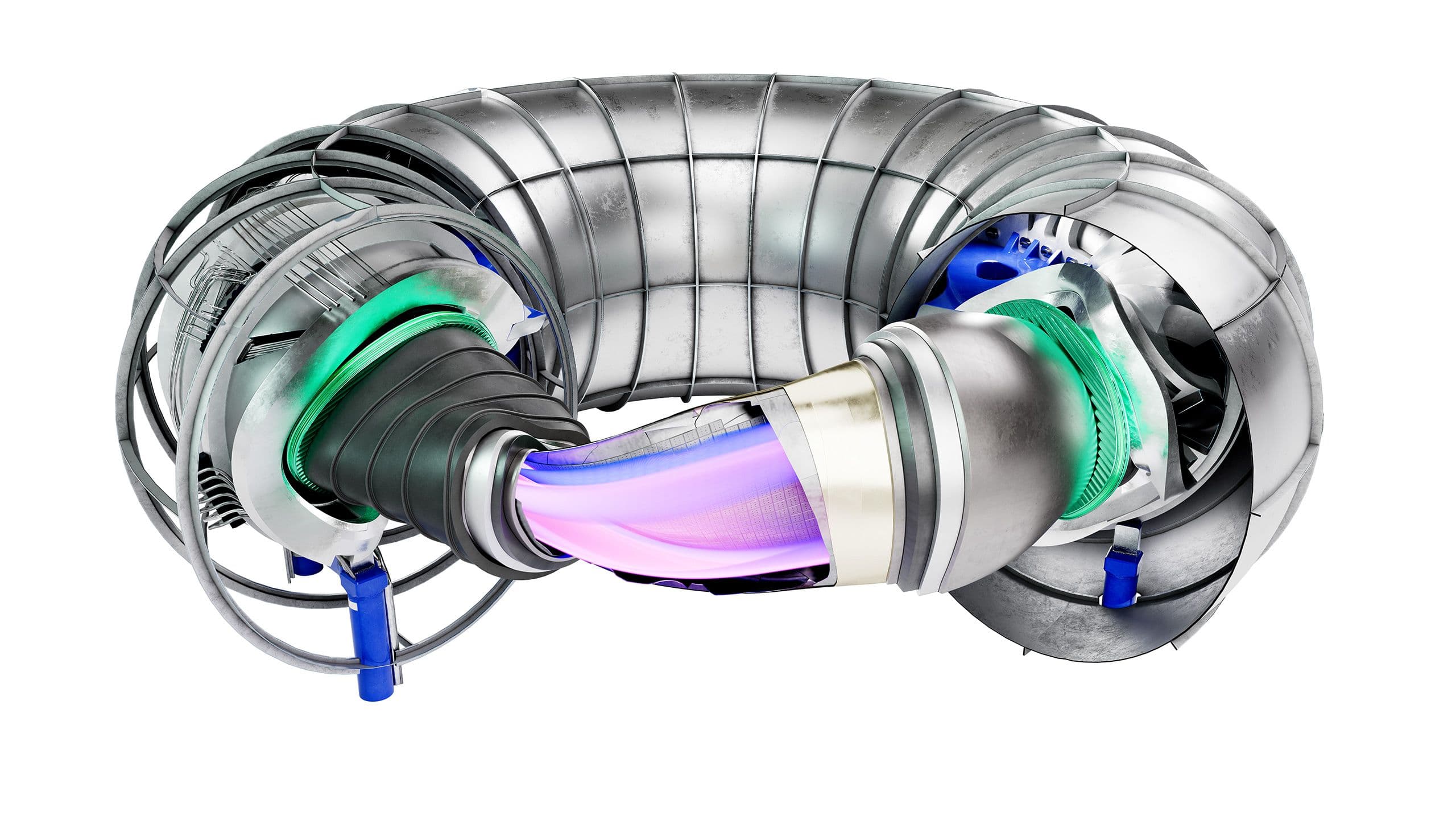

Upside Robotics is turning this convergence into a scalable, field-ready system.

What Upside builds: software-defined agriculture

Fertiliser is still applied the same way it has been for decades. Large sprayers pass over fields once or twice per season, dumping nutrients early because heavy machinery can’t re-enter without crushing crops. As plants grow, access becomes impossible.

Only 30% of that fertiliser is absorbed by crops. The rest is wasted money - fertiliser accounts for 70% of farmers’ input costs - and runs off, polluting our waterways and choking the soil that it’s meant to feed.

Upside flips this model. Their small autonomous robots move through crop rows throughout the growing season, sensing plant health and delivering nutrients only when and where they’re needed. A solar-powered base station sits at the edge of the field where robots recharge and refill. Farmers monitor everything from their phone.

The combination of this reliable hardware with AI software is the real breakthrough. Algorithms interpret weather, soil conditions, crop morphology and growth patterns to determine the precise nutrients plants need each day. Each robot generates tens of gigabytes of data daily, feeding models that optimise variables humans struggle to manage manually.

The results: transformative economics and explosive traction

Farmers using Upside are already cutting fertiliser spend by 70% while increasing yields. On razor-thin margins, this is already transformative. Early data suggests their approach can increase yields by 2-3x.

Critically, the system requires no large capital investment. No infrastructure overhaul, no retrofitting existing equipment. The system will pay for itself within a year.

After just one growing season serving 13 farms, Upside’s waitlist has grown to over 200 farms totaling 500,000 acres - excitement driven almost entirely by word of mouth.

Why this matters now: agriculture under stress

Upside is focused on row crops like corn, where nutrients account for up to 45% of production costs. These crops are concentrated in Canada, the US, and Brazil, and account for over 87% of total crop area in the US alone. Fertiliser prices are volatile, driven by geopolitics and supply concentration. Soil quality is deteriorating. Climate volatility is making decades of farming intuition unreliable.

Upside gives growers control as these variables become unpredictable. Governments increasingly recognise food security as national security. Reducing reliance on imported fertiliser and cutting agricultural runoff are policy priorities, not just environmental ones.

And soon, when Upside independently verifies that its system reduces pollutants, the company and its customers can access subsidy pipelines that make ROI even stronger.

The team: built by people with dirt under their fingernails

Co-founder and CTO Sam Dugan grew up in a Canadian farming family and trained in mechatronics at the University of Waterloo, a robotics talent hub in Canada’s agricultural heartland. Their founding software engineer, Joe Duchesne, spent a decade at autonomous cleaning robot company Avidbots.

Co-founder and CEO Jana Tian brings a complementary background as a chemical engineer who spent years working with growers and food teams at Unilever. Together, they understand both the technical and commercial realities of farming.

Why we invested

As capital floods into AI software with limited defensibility and flashy humanoid robots, Upside is applying these technologies to a sector that urgently needs it, in a way that already works.

It helps farmers produce more food with fewer inputs, improves environmental outcomes and makes a difficult profession sustainable for the next generation.